- Home

- New Kyurizukai

- Architecture and urban design

from Keio's Faculty of Science and Technology

Architecture and urban design

from Keio's Faculty of Science and Technology

Designing spaces that create encounters and liveliness

The attractiveness and diverse expressions of cities

Almazán says he was interested in cities from an early age. He has crossed national borders to visit and research various cities. He began to develop a strong admiration for Japanese architectural design and came to Japan as a research student 15 years ago. He has been shedding new light on Japanese urban research from a global perspective and is now attracting attention by creating unique spaces in regional towns.

Jorge Almazán

Graduated from the School of Architecture of the Technical University of Madrid in 2003. In 2001, he studied abroad at the Technische Universität Darmstadt. He obtained his doctoral degree from Tokyo Institute of Technology. In 2008, he held the position of Invited Professor of Architectural Design at the University of Seoul. Since 2009, he has taught at Keio University, where he is currently an associate professor. He operates “Studiolab,” an architectural design laboratory, and carries out both architectural work and research.

The Research

This issue introduces Associate Professor Jorge Almazán who is contributing to the formation of communities through architectural design.

Revitalizing regional towns through

the power of architectural design

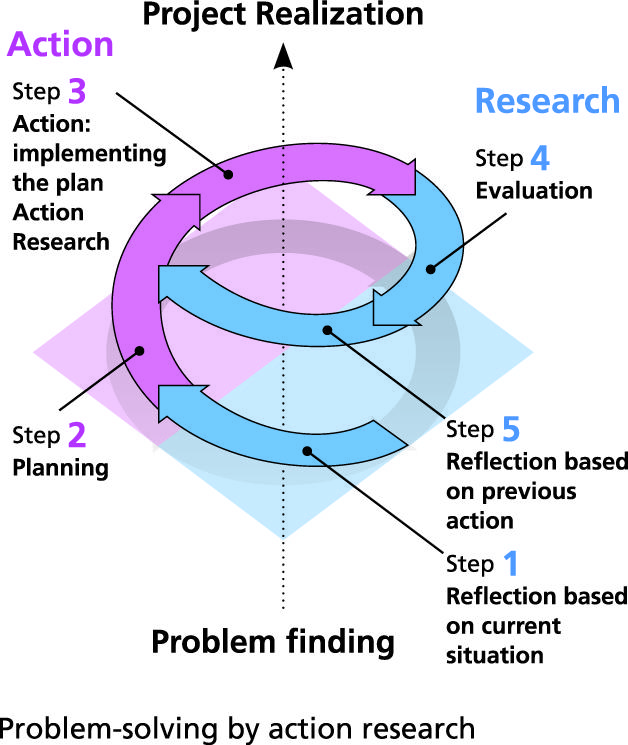

Deploying research methods for practical action research

Currently, various town development projects in various forms are being set up by the residents of regional Japanese towns. In order to restore the liveliness of aging towns with a declining population, having a “place” that acts as a center to foster a sense of community is important. Almazán, who has studied cities around the world, is contributing to new developments in these towns through architectural design.

Designing for activities

Almazán believes that there are 3 important factors in architectural design. These are “form,” “environment,” and the “activities” of people. Originally, the main focus of architectural design was “form,” but since the 1970s, sustainability has become a major social issue, and a need has appeared for architecture that takes the “environment” into consideration.

However, it is hard to say that the “activities” factor has been given enough attention up to now. “I often hear stories of people paying famous architects to design a building, which turns out looking cool, but is difficult to use. This is something we architectural designers must improve on.”

Almazán uses Japanese “engawa” (traditional-style verandas) as an example of an ideal space that successfully incorporates the 3 factors. “All types of engawa are really beautiful, and because of the design of the eaves, they are cool in summer and warm in winter.” In addition, because they are located between the exterior and interior of the building, they function well to connect the activities taking place on both sides without dividing the two. “Different activities are performed depending on the engawa, such as greeting a neighbor who walks by or relaxing with someone while enjoying the view of the garden.”

Designing a space for such activities will not be successful through theoretical considerations alone. It is important to actually set the activities in motion and hold a series of reviews of the outcomes.

To carry out such research, Almazán has adopted a research technique called “action research (activity + theory)” that was proposed by social psychologist Kurt Lewin (see figure on next page). Almazán says that while continuously reviewing the outcomes, one may also notice a deeper theoretical issue hiding behind the scenes.

Experimenting to create liveliness in urban spaces

“I think there will be a lot of demand to design for activities from now on” says Almazán. For projects in regional towns in particular, there is a need for public spaces that foster a sense of community and help revitalize the region. What kinds of designs will realize this?

In urban research up to now, it has been said that in order for public spaces to attract people and create liveliness, the design has to invite people to sit and stay. However, there are few public spaces where one can stay outside sitting in public space in Japan. Almazán attempted to observe the activities of Japanese people on site when they were provided with a public space where they could sit and spend time.

The Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse (Yokohama City, Kanagawa Prefecture), a popular tourist spot, was selected as the location to carry out the experiment. There are shops and restaurants inside the building and it is bustling with people, but the central plaza outside is not used and is often empty. So, 300 moveable chairs were placed in this space. These were chairs used in schools that were no longer needed, colorfully painted at a workshop in which the public could participate to give these pieces of furniture a second life. Unique and attractive chairs were made on a low budget, and these were allowed to be placed anywhere in the plaza (see left photo).

This experiment was conducted in January 2016, and even though it was in the middle of winter, many people sat on the chairs as they wished to enjoy their time, and the space bustled with people. Video recordings of the day were made and the activities of the people were analyzed in detail.

Almazán uses the findings from his research, including those from this experiment, in the designs of actual projects. We will now introduce one of his representative town development projects.

Using research outcomes in town development projects

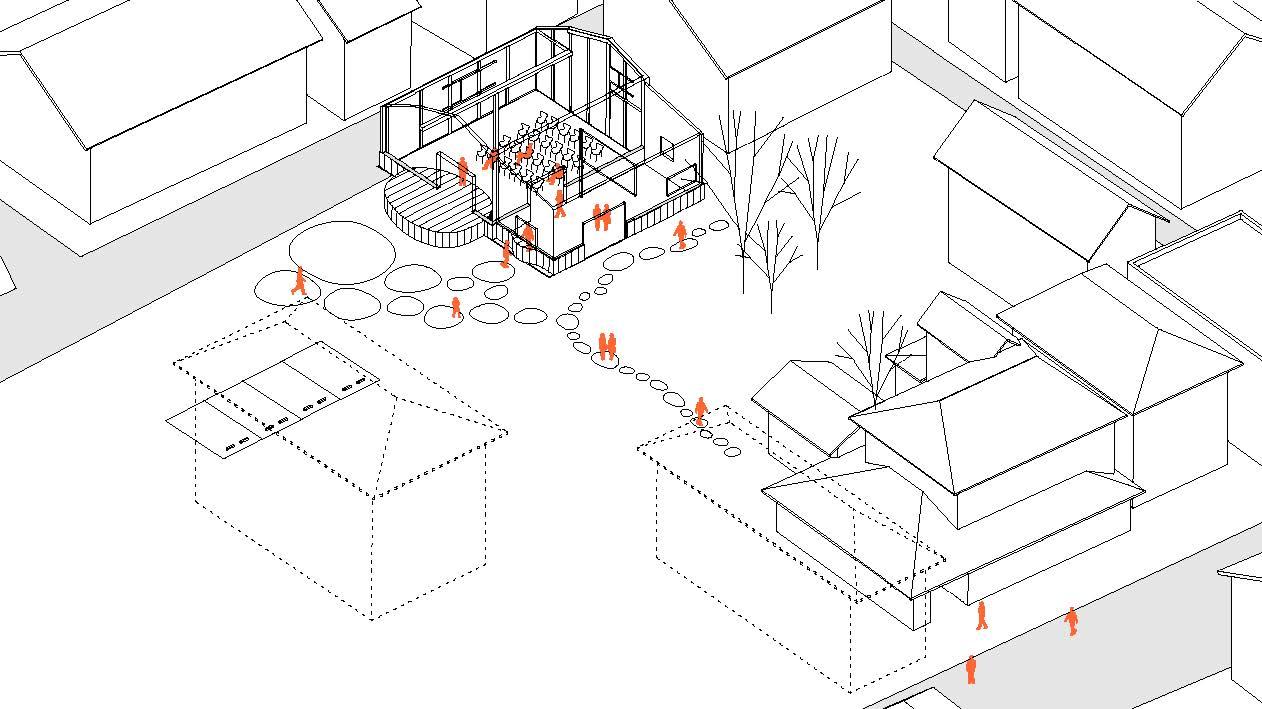

The above photo and drawing are those of the sake brewery on the grounds of the “Former Futabaya Sake Brewery,” a tangible cultural property in the town of Ichikawamisato in Yamanashi Prefecture, which was repaired and converted into a gallery. It was jointly designed with “Ichikawa map no kai,” a local town development organization, with the aim of creating a base for revitalizing the region. Stepping stones are placed between the main building and the stage of the gallery to connect them and allow a variety of activities to take place inside and outside the gallery.

“The chosen site was an old sake brewery from the Edo period, but it was structurally sound and there were no dangers or problems. We could have demolished and constructed a new building, but demolition cost is also high, so we recommended that they renovate and use the original building.” He says that he showed various proposals through models and worked with the townspeople on the design.

The most distinctive feature of this project is the stage that extends from the inside of the brewery to its exterior, but this was not originally planned. It came about from the discussions that took place. After the opening of the facility, various events such as noh plays have frequently been held. It is also popular as a wedding party venue. “I am very happy to have contributed to the region. I can feel the power of architecture,” says Almazán with a smile.

Old sake brewery before renovation

The sake brewery and stage can be enjoyed in various ways

Drawing for examining the flow of people

The sake brewery on the grounds of the “Former Futabaya Sake Brewery”renovated into a gallery

The role of architects is changing

Currently, in Europe and Japan, more importance is placed on renovation, including maintaining and restoring buildings, than on new constructions. Almazán says that this is expanding the role of architects. “I feel that we need to play a role similar to that of social activists, being involved in the operation and management of communities and proposing solutions to regional issues after examining these by ourselves.”

For this reason, Almazán is developing activities at his own laboratory under the 3 pillars of “social action,” “research,” and “learning.”

In particular, Almazán emphasizes the importance of “learning.” “There are many people who think about research and educational programs separately, but I think about them together. This is why I use the word ‘learning’ instead of ‘education.’”

It is my hope that students learn many things while working on actual projects. The efforts made by architects open to learning and not bound by outdated architectural frameworks, will produce energetic projects and lead them to success.

Interview

Associate Professor Jorge Almazán

If you want to be involved with society and people, you choose architecture

I heard that you were born in Spain.

I was born in Alicante, a city in the Valencia region. It is a city facing the Mediterranean Sea and a tourist destination. The weather is nice all year round, and everyone relaxes on the beautiful beaches. You can also eat the best paella in Spain.

It is a compact city with various other features. We have a university, and it is also a cultural center with many exhibitions and events taking place.

What kind of childhood did you have?

I loved to draw and read. I was a boy who liked art, and I even made a movie (short film). I wanted to draw every day, and I did think about a career as an artist, but I also had a strong desire to be involved with society and people, so in the end I chose architecture.

To design a building, there are things like laws and regulations, structural calculations, and installations that you must learn, but art is also a factor, and most of all, architecture is it’s a collaborative effort that involves many people.

What did you study at university?

I studied at the Technical University of Madrid, which was established in 1971 when 2 technical schools originating in the 18th century that specialized in engineering and architecture merged. It has a long history in the field of architecture. Unlike in the Japanese system, the university has 7- or 8-year degree programs, and you are a certified architect when you graduate. I thoroughly learned the basics of architecture here.

While at the Technical University of Madrid, I studied abroad for a year at Technische Universität Darmstadt in Germany. Darmstadt is a city famous for Jugendstil architecture, known as Germany’s Art Nouveau.

This study abroad was part of the EU’s Erasmus Programme (ERASMUS: European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students), which is a grant program to facilitate student exchange. The EU is attempting to build a kind of state that hasn’t existed to date based on the philosophy of a unified Europe, and for this, exchange of personnel is very important.

Many EU students use this program to build international friendships, and it is normal for them to be able to speak 3 languages (mother tongue, English, and the language of the country they study in).

Study abroad in Japan and surprise by the lack of “public spaces”

Then you came to Japan.

I learned about German architecture and cities at Darmstadt, but I also wanted to learn about non-European architecture. Japanese architects are popular internationally. Many young architects around the world have learned from works such as those by Kenzo Tange, Kisho Kurokawa, Tadao Ando, Toyo Ito, and Kazuyo Sejima. I don’t know how much the Japanese people are aware of this, but Japanese architectural design is top-class in the world.

While I was thinking about studying in Japan, I happened to meet Kazuyo Sejima at a workshop. When I found the courage to consult her about studying in Japan, she helped me with my application for the Monbukagakusho Scholarship, and 2 years later, I was admitted to Professor Yoshiharu Tsukamoto’s laboratory at Tokyo Institute of Technology as a research student. I gained good experience at Professor Tsukamoto’s laboratory, as I got to do practical work including taking part in design competitions and being involved in designs.

What impressions do you have of Japanese cities?

What surprised me the most was the lack of public spaces. There are no benches or urban squares. When I asked Japanese researchers why there are no urban squares in Japan, most of them said “cultural difference.” They say that “interior spaces are more suitable for Japanese people than expansive outdoor spaces,” but if you look at ukiyo-e pictures of Nihonbashi during the Edo period, isn’t it bustling with people? People have also said “because there are mosquitoes,” but there are mosquitoes in Spain and Italy too (laughs).

Japanese tourists sightseeing around European towns seem to enjoy open cafes and relaxing in town squares. I think that the lack of open spaces in Japan is not a cultural issue, and this led to an experiment at the plaza in front of the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse (see introduction of research).

You decided to explore that question deeper.

Firstly, I investigated what activities people carry out in cities, and what kind of spaces are used for these activities. Then, contrary to urban squares, I found widespread use of spaces not common in Europe.

These were spaces that were like an extension of the home. In commercial areas centered around stations, there are spaces where you can spend time like at home, such as manga cafes, karaoke boxes, game centers, saunas, and “super sentos” (large public baths with various facilities including restaurants). Izakaya (Japanese bars) with private rooms are also popular. Outdoor spaces such as urban squares are not used so much, but various activities take place within these commercial spaces.

Not only does the meaning of “public space” differ, but the way “homes” are used is also different. For example, many Westerners often host home parties where friends gather to have a good time, but Japanese people seem to gather at restaurants outside rather than at somebody’s house. This creates a middle ground between the home and public spaces.

Comprehending the energy of Japanese cities that is absent in Europe

What can be said at the architectural and city levels?

I find zakkyo buildings (multi-tenant buildings) very interesting. There are no zakkyo buildings in Europe. In European commercial areas, shops are located on the 1st floor, but in zakkyo buildings, restaurants may be on the 7th floor, which feels very strange to me. When you examine various zakkyo buildings, you begin to see a typology.

In terms of cities, we focused on commercial areas centering on stations. If you look at areas within a 5-minute walk or a 500-meter radius from a station, you will find that they are made up of several matching elements such as side streets, entertainment districts, and shopping areas. You will see this same pattern at any station, whether it’s Shibuya, Ikebukuro, or Shinjuku, and we can say that this is so because the city is responding to the social need for a space that overlaps living and commercial spaces.

I think that comprehending Tokyo’s energy from the perspective of things that “exist in Japan but not in Europe” has allowed me to carry out research that has originality.

In a series of projects in regional towns that you have been working on recently, I feel that you have been incorporating open-space activities into the design of public spaces.

There is a concept called “glocal” that tries to realize localness through global means, but I like the word “translocal” in the sense of learning from many localities.

In the “Former Futabaya Sake Brewery” project, I introduced the localness of spaces like plazas in my hometown of Alicante that I had learned while growing up there to a different locale in Yamanashi Prefecture (see introduction of research). In Yamanashi Prefecture, they have their own materials and craftspeople. So, we have to come up with a concept that makes use of these materials and skills. But more than that, by thinking about things with an attitude of learning from the two locales, you will be able to get “translocal” inspirations.

We used traditional Japanese materials for the building, but a Mediterranean mindset can be seen in the program being developed there. I think it’s okay to open up various possibilities in a space rather than being narrow-minded, saying it must be this way because it’s in Japan, or it must be that way because it’s in Spain.

Experiencing the kindness of people within Keio University and its reputation outside

What are your impressions of Keio University as a faculty member?

What are your impressions of Keio University as a faculty member?

The Faculty of Science and Technology seems to have a warm culture. Again, it’s all about human relationships. The administrative staff and other faculty members are all very kind. Without such relationships, I think it would be very difficult for foreign faculty members to get by.

In addition, what I feel while carrying out research is the good reputation that Keio University has in society. Even when you meet people for the first time, including public and civic organizations, they are willing to talk to you when they hear the name of the university.

I heard that “Keio Architecture” was established as a base for the architecture courses.

Keio University has a history of having great architects such as Shigeru Ban, Kengo Kuma, and Kazuyo Sejima teach at the university while working as architects. Currently, education and research related to architecture are carried out at the Faculty and Graduate School of Science and Technology (Yagami Campus), Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Faculty of Policy Management, and Graduate School of Media and Governance (Shonan Fujisawa Campus: SFC). In 2018, “Keio Architecture,” an education and research base jointly operated by these faculties and graduate schools was established. It is organized in a way that allows 12 faculty members to closely work together to drive the creation of new architectural designs that conform to world standards. Regardless of which faculty students are enrolled at, they are eligible to take the examination for 1st-class architect certification.

Please give some advice to young students aiming to become architects.

Developing your passion is very important. If you like something, please spend time to get better at it. From there, you will be able to find your research theme or discover your design style.

Architecture has a clearer social orientation than art. It also costs money. So, even students have to be aware that they are members of society and act responsibly. I would like to see all of them become architects who passionately contribute to society.

Some words from Students

● I studied abroad at the Technical University of Madrid for about three months. I felt reassured because I got a lot of support from Associate Professor Almazán. He is very organized and supports our thesis and research projects with great care. We are close with him so it is easy to consult him on even minor issues. There are many overseas students in his laboratory so it has an international atmosphere. (1st-year master’s student)

●I am happy that in addition to theoretical research, we get to work on actual projects with the support of his laboratory. When students propose research themes and designs, he focuses on the good parts and gives us advice, allowing us to develop these further. Things don’t always go as planned, but he is very patient and gives us time to work things out. (1st-year doctoral student from the University of Alicante)

●I was very surprised when I first met him because he knew more about Japanese history and urban planning than Japanese people. He brings to light things we would tend to overlook because it just feels so normal, from a fresh, international perspective, so that we can make new discoveries. His explanations when comparing various cities around the world are easy to understand, and he has encouraged me to think about Japanese cities from a much broader perspective. (3rd-year doctoral student)

(Reporter & text writer: Yuko Hiratsuka)