- Home

- New Kyurizukai

- The World of Language and Speech

from Keio's Faculty of Science and Technology

The World of Language and Speech

from Keio's Faculty of Science and Technology

How do we humans understand each other?

I changed my specialization to phonetics while studying in the U.S. Encounters with people from diverse fields helped to deepen my academic pursuit.

As a junior high school student, Dr. Sugiyama was first exposed to English and became interested in differences among languages, which paved the way for going into linguistics. She went on to graduate school in the United States to study semantics, but her interest soon shifted to phonetics. She was attracted to phonetics because, unlike other areas in linguistics, the target of analysis, waveforms, has a physical reality, which can be objectively separated from the analyzer. Upon returning to Japan, she joined her alma mater Keio University, where she currently serves as an English language teacher while also conducting research in an interdisciplinary environment.

Yukiko Sugiyama

is a linguist who specializes in phonetics. Mainly using Japanese as the target language, she studies speech communication by analyzing speech data and conducting perception experiments. She was born in Aichi Prefecture and completed her bachelor's degree in English and American literature at Keio University. She completed her master's course in linguistics at University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, and obtained her Ph.D. in linguistics in 2008 from the same institution. In 2009, she joined Keio University as an assistant professor at the Department of Foreign Languages and Liberal Arts, the Faculty of Science and Technology. She is also a member of the Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies at Keio University. In 2016, Dr. Sugiyama was promoted to her current position as an associate professor. In 2017, she was honored with the Best Lecturer's Award.

The Research

Associate Professor Yukiko Sugiyama is featured in this issue,whose field of research is phonetics focusing on the mechanism of speech and hearing.

I’d like to unravel the mechanisms of

our speech and hearing

Investigating what characterizes word recognition

We utter words when speaking, but it’s impossible to physically utter the same words twice even if the words are the same. If so, how do we recognize the words spoken to us, understand their meaning and communicate with one another? Or is it possible to distinguish words such as “hashi(bridge)” and “hashi(edge)” that are pronounced likewise but have different meanings in Japanese? Associate Professor Yukiko Sugiyama approaches the process and mechanism of speech production and perception from both aspects: words uttered by the speaker and their perception on the part of the listener.

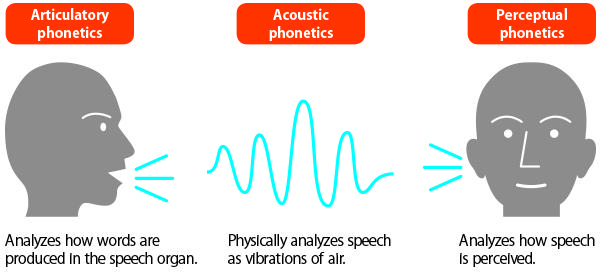

What is “phonetics”?

Dr. Sugiyama’s specialty is a field of study known as “phonetics.” Phonetics is largely classified into three academic areas (Fig. 1): “acoustic phonetics” examines physical properties of spoken words; “articulatory phonetics” analyzes how speech sounds are produced in the oral cavity when humans speak; and “perceptual phonetics” investigates the process by which humans perceive speech.

“Phonetics is often regarded as a branch of linguistics. However, in order to examine speech, we need to identify its physical characteristics such as duration, frequency and intensity. Also, articulation deals with the workings of the oral cavity and vocal folds while speech perception concerns the human sensory mechanism. These factors require knowledge from a wide range of disciplines including physics, engineering, medicine and cognitive psychology, among others. It isindeed a multidisciplinary field involving both humanities and sciences,” explains Dr. Sugiyama.

With phonetics as the base, Dr. Sugiyama takes a two-way approach in proceeding with her research. One way is to analyze the physical characteristics of speech, and the other is to examine how a person perceives speech. By using this two-way approach she’d like to unravel characteristics of the Japanese language.

Fig.1 Phonetics

Phonetics is largely classified into three areas as shown below:

Looking for characteristics that distinguish words

“The target I use for this purpose is Tokyo Japanese, or so-called the Standard Japanese. I collect and record samples of speech from Tokyo Japanese speakers. To begin with, I examine the physical characteristics of speech such as the frequencies and durations of speech segments. In the case of the Tokyo Japanese, for example, the word ‘ame’ (rain) is pronounced with a higher pitch for ‘a’ and a lower pitch for ‘me.’ On theother hand, the word ‘ame’ (candy) is pronounced with a lower pitch for ‘a’ and a higher pitch for ‘me.’ In other words, the pitch levels of high and low determine the meaning of words.”

But what if it comes to “hashi” (meaning “bridge” and “edge”) and “tori” (meaning “bird” and “last performer”)?

“Both words are pronounced with the same pitch pattern of low-high, making it difficult to distinguish them. However, when you say ‘hashi o aruku’ (the former meaning ‘walk over a bridge’ and the latter ‘walk along the edge’), the postpositional article ‘o’ that follows ‘hashi’ is pronounced with a low pitch for the former and with a high pitch for the latter. By putting words of interest in an environment where they minimally differ, we find out the characteristics that people use to identify words,” she continues.

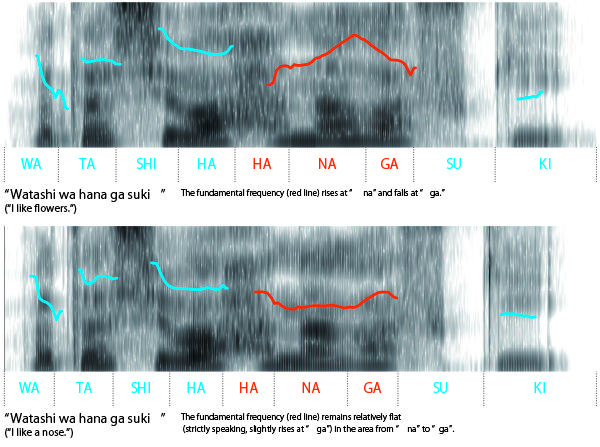

As a matter of fact, if we analyze the frequency components in one’s speech and look at their spectrogram – the so-called “voiceprint” – we see rises and falls of the fundamental frequency (the rate at which the vocal folds vibrate per second, which we perceive as pitch) which serve to distinguish words (Fig. 2). Thus, in Japanese, we use pitch accent to distinguish one word from another.

“In terms of distinguishing words by the movement of fundamental frequency, Japanese is similar to Mandarin Chinese, which is classified as a tone language. Meanwhile, the function of pitch in Japanese is similar to that of stress in English.”

Some propose that Japanese pitch accent is characterized not only by fundamental frequency but also by intensity and duration of segments as is typically observed in English and other stress accent languages.

“I don’t think that fundamental f re quenc y a lone is suf f icient to distinguish between words in robust communication. In fact, English stress accent includes multiple elements such as intensity, duration and pitch. However, the meanings of Japanese words change if segment durations change. Then what elements can be used as acoustic correlates of pitch accent in Japanese?

This weighs on my mind,” Dr. Sugiyama remarks.

To address this problem, Dr. Sugiyama conducts p erception exp eriments using edited speech from which the f undament a l f re quenc y has b e en artificially removed. If listeners can successfully distinguish words such as “hashi” (bridge) and “hashi” (edge), even when there is no fundamental frequency, it would suggest that acoustic cues other than the fundamental frequency are present in the speech, enabling the listeners to use them to identify the words they heard.

Dr. Sugiyama says, “The results found that the listeners were over 95% correct in word identification when they heard natural speech. For the edited speech which contained no pitch information, the accuracy dropped to roughly 65%, but it was above chancel level. This leads to a conclusion that Japanese pitch accent is realized by certain other acoustic characteristics in addition to the fundamental frequency.”

For future research, she would like to ident if y exac t ly what acoust ic characteristics listeners use to identify words when there is no fundamental frequency.

Fig.2 Voice pitches and difference in meanings

The dark areas with vertical striations are spectrograms (the so-called voiceprint). The vertical axes indicate frequencies (Hz). In the spectrograms, the darker an area, the greater the amount of energy. The blue and red lines lying on top of the spectrograms show pitch contours (Hz).

Would like to contribute to machine-based speech recognition and synthesis

In what way do these studies benefit us socially and academically?

“Academically, I think my research would contribute to a better under-standing of the possible prosodic types that human language can have by revealing the acoustic details of Japanese pitch accent.”

“I think it would also contribute to improving speech recognition systems and speech synthesis by indicating what acoustic correlates accompany pitch. In order to raise the accuracy of these systems, are there any other acoustic elements that need to be taken into consideration? If we can find an answer to this question, it will also help to synthesize more human-like speech,” remarks Dr. Sugiyama.

While hearing aids and cochlear implants are very helpful to those who need them, their performance is still far from that of an actual human ear, causing difficulty in sensing pitch, having a narrower dynamic range, and introducingnoise into what we actually want to hear. This is why hearing performance closer to the human ear is sought after.

“Also, the ability to recognize speech is known to vary largely from one person to another and much remains unsolved. For example, you can hear your name mentioned somewhere all of a sudden even when you are talking to someone in a noisy environment, a phenomenon known as the ‘cocktail party effect.’ Individual differences in perception mean that there is much more to be understood about the physiological details of pitch perception. To address these questions, it is necessar y to collaborate with researchers from the engineering field, which will greatly help to formally characterize the acoustic details of speech.”

In order to learn the methods used in signal processing, Dr. Sugiyama has sat in on an applied mathematics class together with second year students and gets help from a student whenever she has questions from the class. Dr. Sugiyama’s challenge continues.

Interview

Associate Professor Yukiko Sugiyama

Exposure to the fun of English-the origin of my pursuit of phonetics

How did you spend your childhood?

Born in Aichi Prefecture, I was raised in a family of four: parents, a younger brother and myself. When I was young, I was a going-my-way type of precocious girl who would say, “I’m attending kindergarten just to kill time,” which surprised adults around me (Laughter). I was bad at group activities such as collective playing/dancing and practicing for an athletic event.

Speaking of my personality, while I am similar to my mother in some aspects, I have much more in common with my father. With an engineering background, my father worked for an electrical manufacturer. I guess I can say I overlap with him to some extent career-wise as well.

Did you have difficulties because you were bad at group activities?

I attended private school offering combined junior and senior high school education, where I was comfortable thanks to its liberal school culture.

I became interested in English when I first learned it in junior high school. This is the origin of my interest in language. I must also mention the book titled “kotoba to bunka (English title: Words in Context)” authored by Takao Suzuki, some of which was cited in a textbook I used in high school. I was inspired by cultural differences found in different languages.

For example, Japanese vocabulary is relatively limited regarding manners of motion such as “walk” and “run.” By contrast, English vocabulary is very rich. In addition to “run,” it has words such as “scurry,” “scuttle” and “trot," which express minute differences in terms of how these motions are carried out. On the other hand, Japanese vocabulary is quite rich in mimetics. The world may look different due to differences in the ways different languages express things. This aroused my interest in languages.

I entered Keio University wishing to learn about languages from a scientific point of view. Although Keio had no independent linguistics department, it offered linguistics studies within general education. In fact, a variety of linguistics-related classes were available. Another advantage was that I was able to take classes of professors from the Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies on the Mita Campus.

Did you take part in any club activities?

I first joined the Keio English Speaking Society club, but I quit after only one year because it was a little too time-consuming. Practices and stage-making work for the inter-college English theatrical performance contest took so much time. Then I joined an inter-college international exchange organization. At the organization, we organized camps and invited students from foreign countries to discuss various international issues. Through the organization’s exchange programs, I visited the Philippines and Norway myself. These activities were valuable opportunities for me to directly learn about foreign cultures and how people with different backgrounds communicate with others.

Going on to graduate school in the U.S. z to pursue my interest in linguistics

Was it your initial intention to choose a researcher’s career?

Not at all. I had been thinking that I would find employment at a corporate company upon graduation. But near the end of the third year, when students in Japan start job hunting, I just didn’t feel that way. At the same time, I did not know if I could do anything to contribute to the society as a researcher. When I talked to my academic advisor, he said, “At the beginning, I myself was not confident that I could become a respectable researcher but dared to advance to graduate school. So, if you are interested in an academic career, why not pursue it?” With this advice, I made a decision to go to graduate school. Although my mother was originally against my going on to graduate school and going abroad to study, I finally convinced her (or I had her give up, you might say). In the summer of the year I finished college, I flew to the United States to study at the University at Buffalo, the State University of New York (SUNY at Buffalo).

There were three reasons for why I went to the U.S. to study linguistics. First, there were practically no universities in Japan where I could learn linguistics systematically. Second, when I was taking linguistics classes at Keio, many of the professors who taught me had their Ph.D. from graduate school in the U.S.. Third, the linguist I wanted to work with at the time was at SUNY at Buffalo.

In the beginning, I was interested in semantics. However, my interest gradually shifted to phonetics, my current research theme. With semantics, I often found it difficult to analyze the data objectively because my judgement intervened in the analysis. By contrast, approaches used in phonetics were clear-cut because no matter how subjective you might become (you should try not to though), the object that you deal with has a physical reality. The object of analysis is clearly separated from the analyzer.

Studying in the United States brought with it a number of valuable encounters. There was an overseas student who came from Togo on a scholarship from her government. When I saw her very humble lifestyle, I could really feel my privileged environment. On another occasion, a student from Saudi Arabia told me about the strict control of freedom of speech in his country. Through these experiences, I literally felt the diversity of countries and their cultures.

My research life in Buffalo lasted as long as nine years partly because I shifted my specialization to phonetics along the way. I returned to Japan in 2008.

I was fortunate enough to be able to join the Faculty of Science 2 and Technology at Keio University.

After serving as a part-time lecturer for Waseda University, I joined Keio University in 2009

My affiliation at the Faculty of Science and Technology has been an advantage in terms of my research as well. Last year, I sat in on an applied mathematics class to learn the basics of signal processing, such as the Fourier transform, and asked one of the students who took my class before to help me keep up with the class. In this faculty, students and the faculty members work closely and they take good care of their students.

My return to Keio has also provided me with delightful opportunities to work together with Prof. Masumi Kindaichi (now an Emeritus Professor), who was a lecturer for an NHK Russian language program on the radio, which I listen to as an undergraduate, and Prof. Kyoko Ohara, who I asked for advice before going to the United States to study.

For the past several years, I have been helping out with the workshop called “My Voice” which Prof. Shigeto Kawahara at the Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies organizes. This workshop introduces how to use “My Voice,” software which can be downloaded free on the Internet. With this software, you can communicate with your family using your own voice even if you have lost your voice or cannot speak due to illness. You will need to record your voice (vowels and consonants) beforehand though.

In your daily life, you may seldom become conscious of your own voice, but it is a very important part of your identity. Through this workshop I’ve come to think so more strongly than before. I’d like more people to know “My Voice” and make good use of it.

How do you spend your days off?

I refresh myself mostly by trail running and climbing mountains. In short, trail running is running in mountainous areas. My favorite places not far from where I live are the Takao and Tanzawa mountains. I plan several routes beforehand using a map, and leave home early in the morning to go trail running. It's really refreshing to run through scenic areas in a superb natural environment.

Some words from Students

Student : Interest in “voice” led me to take Dr. Sugiyama’s class. She is gentle but passionate when teaching us. One of the examples of her unique teaching style is that she sometimes lets students play the role of teacher. Meanwhile, she enjoys the students’ class together with other students. Dr. Sugiyama introduced the “My Voice” workshop to me, which I’m helping with editing the recorded speech. Collaboration with medical doctors and occupational therapists is expanding my view of the world.

(Reporter & text writer: Madoka Tainaka)